1900s: Seattle Electric Co. Workers with wagon, Seattle.

Seattle, March 1903. Crowd surrounding streetcar during strike against Seattle Electric Co., in front of Bon Marche, 2nd Ave. and Pike St.

In 1903, Local 217 sent H. A. Patton as the Local Delegate to the 8th International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Convention held in Salt Lake City, Utah. There was no roll call number (the number of members in the Local,) so we don’t know how many members Local 217 had at this time.

In 1905, Brother W. W. Morgan was the Local 217 Delegate to the 9th International Convention held in Louisville, Kentucky.

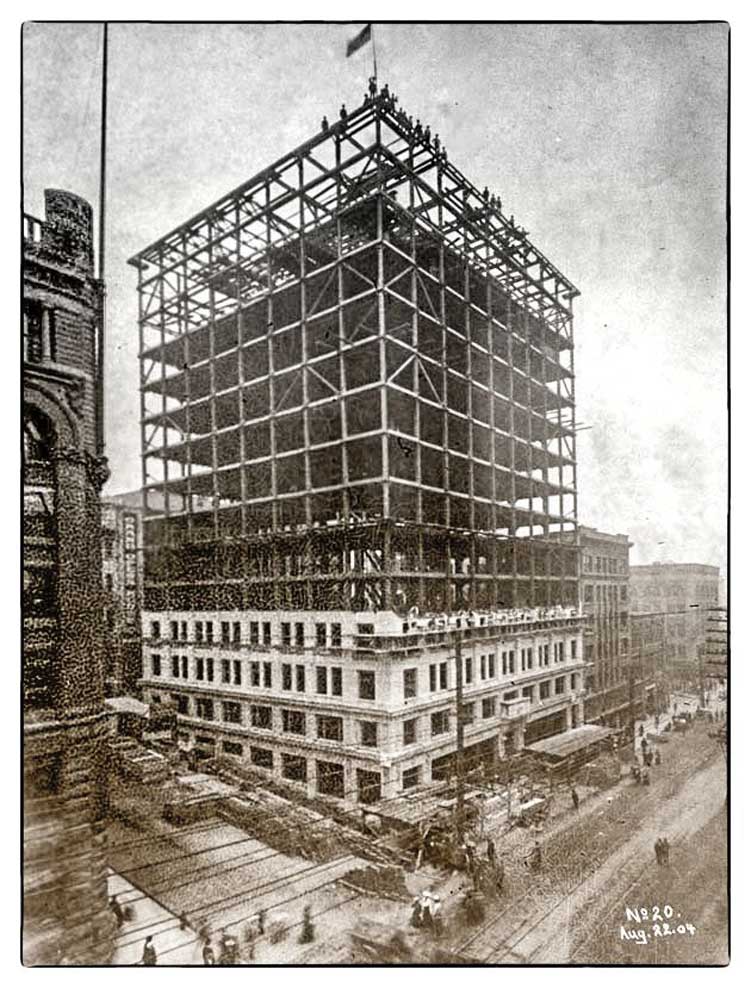

In 1904, the Alaska Building at 2nd and Cherry opened.

In 1904, the Alaska Building at 2nd and Cherry opened. This was the first Seattle high-rise at fourteen stories tall. Today, this building still stands and is a high-end hotel. We think one could assume that some Local 217 wiremen worked on that early building in the sky.

In 1909, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies) began a free speech fight in Spokane. The city had passed an ordinance banning speaking on the streets, the ordinance was directed at the IWW organizing. So Wobblies would stand on soapboxes and begin to speak and then quickly be arrested. Soon the jails were full with 500 IWW members and their supporters. It took some months, but the City of Spokane revoked the ordinance and released everyone from jail.

Object reference not set to an instance of an object.

Local 217 election results held December 1910: Thomas E Lee, Business Manager; H. E. Lee, President; WW Morgan, Vice President; George L Coe, Recording Secretary.

There is one minute book from Local 217 dated from November 29, 1910 to October 3, 1911. The following are some excerpts from that minute book. The Union met weekly with meetings commencing at 8:00 p.m. and lasting sometimes until midnight.

The National Labor Relations Act wasn’t passed until 1935. So the members of Local 217 took it upon themselves to enforce their working conditions, with no protections of any kind. Solidarity of the members holding the Union together.

It was decided at another meeting that when a contractor or shop hired one journeyman, a helper could be hired. When another three journeymen were hired, another helper could be employed.

In October 1911, members assessed themselves 25¢ per month, for a period of three months, for the McNamara Defense Fund.

The McNamara Brothers were two Union Iron workers accused of, and eventually plead guilty to, blowing up the Los Angeles Times building in 1910. The Publisher, Harrison Gray Otis, was vehemently anti-Union and fought the Unions any chance he could. The Defense Fund became quite large and Clarence Darrow, lawyer and leading member of the ACLU, defended the brothers. The brothers were jailed in San Quentin prison. One brother died in prison, and the other, after release, went back to organizing Iron workers. Read on!

1913 The Smith Tower under construction.

Object reference not set to an instance of an object.

Value cannot be null. Parameter name: source

Local 217, the predecessor of Local 46, was issued a charter on December 23, 1901.

Seattle, in 1901, had a population of approximately 81,000 people. It was only eleven years after the Great Seattle Fire, which destroyed most of downtown, and only ten years since the NBEW formed in St. Louis in 1891.

Local 217 was the Inside Local in Seattle from 1901 until 1914, but became defunct in the eyes of the IBEW in 1909. In 1908, the IBEW had a rift in the International Union, known as the Reid-Murphy Split, named after the officers elected by the seceding faction.

The split was the result of several long brewing issues. There was tension between the line side and the wiremen side of the Union; problems with the Grand Treasurer, who had been removed from office for irregularities; and then indications that some employers wanted to see the fast growing electrical Union wrecked!

The Brotherhood went through six long years of division and bitterness. In the end, the AFL (American Federation of Labor), tried to work with both sides of the split, recognized President McNulty and Secretary Treasurer Collins as the official IBEW Union and officers. A court decision in 1912 was the turning point in the rebellion, by declaring the seceding convention to be illegal. It is generally recognized that fully three-fourths of all the electrical Locals in the United States and Canada supported the seceding faction at some time during this period.

Though Local 217 was not affiliated with the International from 1909 until April 1914, it functioned like any other Local Union in Seattle, being part of the Central Labor Council, State Labor Council, Building Trades Council, Metal Trades Council and paid per-capita to an organization called the Pacific District Council, which was a governing body.

The first mention of Local 217 in any publication was in the Electrical Worker, the official publication of the IBEW nationally. The publication mentioned the meeting site of the fledgling Local 217 in the January 1902 publication.

Object reference not set to an instance of an object.

In 1909, twelve thousand trade unionists marched through downtown Seattle on Labor Day, parading but also protesting the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition Company and its open shop policy for the construction of the site at the University of Washington. Though the company hired many Union construction workers, Labor still called for boycotting the Exposition.

Object reference not set to an instance of an object.

In 1910, the Business Manager’s salary was $32 per week, increasing to $35 per week in February 1911.

Local 217 paid the Seattle Labor Temple Association $13 for Hall rent and IBEW Local 77 $37.50 for office rent.

An entry in the January 24, 1911 meeting instructed the Recording Secretary to write to the Senator and Representatives of the District, by request from the Eight Hour Day Committee, in regards to the eight-hour day for female workers.

On February 27, 1911, it was adopted in the By-Laws, under Work Rule 11, that no member works on Labor Day under any circumstances. We have to remember that at that time, as far as we know, there were no written agreements with the employers and there was also no Labor Law.

The National Labor Relations Act wasn’t passed until 1935. So the members of Local 217 took it upon themselves to enforce their working conditions, with no protections of any kind. Solidarity of the members holding the Union together.

1912 Touring car in front of the Seattle Times Building

Local 217 had thirteen years of existence and we thank those early pioneers of our Union for their solidarity, determination and grit. It was not easy to be a Union member in those early years; the risk was great and the rewards limited.

The next 100 years wasn’t so easy either, but we owe much to these early Brothers, Sisters and their families for paving the way for our Union to exist today. Read On!

On display at the Hall. One of the original booklets used by IBEW Electricians.

Anna Louise's first endeavor in Seattle was to obtain a seat on the Seattle School Board. Supported by pro-labor factions, women's organizations, and a solid reputation from her work in the child labor movement, she promised to bring a woman's point of view to education politics.

“In what was then a neighborhood of hotels and apartments Seattle’s Labor Temple opened in 1905 at the northeast corner of 6th Avenue and University Street. (Photo courtesy Lawton Gowey). Locals 217 and 46 had offices in this building."

1919. As America’s labor shortage became increasingly serious, women, like these Shipyard workers, began filling more and more non traditional positions, some of them even wearing pants for the first time. Photo Courtesy PSNM

Your current browser is missing features this website requires to display correctly. Please upgrade your browser for the best experience.

TOWN HALL ZOOM REGISTRATION LINK

REMINDER NOTICE:

THE MARINE UNIT MEETING WILL BE MOVING BACK TO

THE FIRST WEDNESDAY OF THE MONTH @ 5 PM IN THE EXECUTIVE BOARD ROOM

anew apprentice resource center link

anew apprentice resource center link![]()